Range of Light Photography | Range of Light Photography™ | News | Middle Fork of the Salmon River

Middle Fork of the Salmon River

While the middle of July found me still waiting out the late season's summer snow-melt and what was then being reported as legendary clouds of mosquitoes in the Sierra high country, I made the "mistake" of checking river water levels on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, in central Idaho. It was still going strong at a nearly ideal 2.5 feet on the Midddle Fork Gauge after a healthy northern U.S. Rocky Mountain winter snow-pack. Two and a half feet ensures a decent flow through the pooled portions of the river, plenty of action in the rapids, exposed sandbars on which to camp, and reasonably manageable hydraulics with a heavily provisioned boat. A bit of history may be called for here...

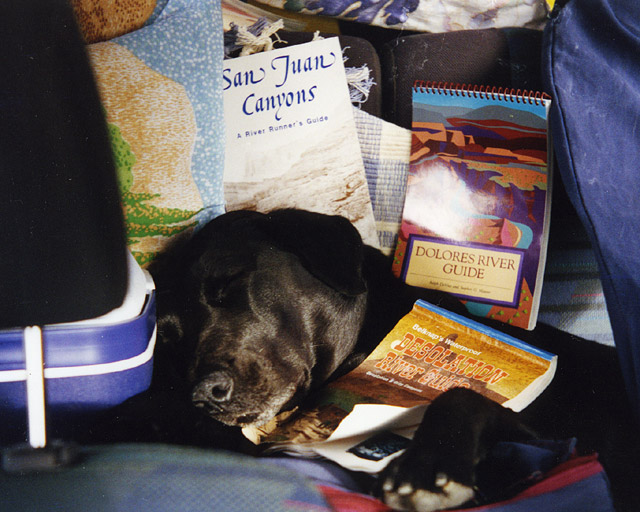

I have been an enthusiastic whitewater kayaker for 25 years, having run nearly all of the major rivers west of the Continental Divide. My first decade of boating was spent in ever more challenging Class V shoals in California's world class whitewater with partners whose risk judgements became, from both objective and subjective criteria, shall we say, increasingly suspect. It became clear to me that it was "safer", in many respects, to leave wanton Class V+ lust behind and to begin kayaking without companions. In the early  1990's I began exploring large western rivers outside of California, which required multiple days of self-support, carrying all necessary gear in the stern of my boats. I say "exploring" reservedly, because while in most cases river guides had been published for these trips, I was alone and totally self-sufficient on what was otherwise unknown (to me) water. I ran the Upper and Lower Colorado, San Juan, Yampa, Green, Dolores, and Bruneau/Jarbidge river systems

1990's I began exploring large western rivers outside of California, which required multiple days of self-support, carrying all necessary gear in the stern of my boats. I say "exploring" reservedly, because while in most cases river guides had been published for these trips, I was alone and totally self-sufficient on what was otherwise unknown (to me) water. I ran the Upper and Lower Colorado, San Juan, Yampa, Green, Dolores, and Bruneau/Jarbidge river systems  (and their tributaries), to name a few - all as multi-day, solo self-support trips. Class V rapids, though few and far between, were more than compensated for by miles of placid floating through both beautiful, remote and historical scenery. I had previously run America's other premiere multi-day rivers, the Colorado through the Grand Canyon and the Selway in Idaho with raft support, but regrettably had never been able to get onto the similarly highly controlled, reservation booked, Middle Fork of the Salmon River. Boating solo freed me from the hassles of raft support and the uncertain personalities of trip-mates. In 1993 I obtained a released midsummer reservation and was finally able to notch another great river with 6 days gear crammed into the oxymoronically termed stow-floats within my thunder blue Perception Dancer kayak. Calling in for cancelled permits, and having the freedom to go at will, enabled me to run the 100 mile river every few years as a kind of summer retreat. While the accommodations were spartan-like to be sure (especially when compared to the lavish ice-cooler, gourmet catered, air-mattressed - not that there's anything wrong with that! - $2500 commercial raft expeditions), the freedom of independence and relative solitude in this scenic river wilderness simply could not be beat. I'd repeated the journey a total of five times over the intervening years, until this summer it dawned on me that seven years had passed without dipping a paddle into its crystal clear waters.

(and their tributaries), to name a few - all as multi-day, solo self-support trips. Class V rapids, though few and far between, were more than compensated for by miles of placid floating through both beautiful, remote and historical scenery. I had previously run America's other premiere multi-day rivers, the Colorado through the Grand Canyon and the Selway in Idaho with raft support, but regrettably had never been able to get onto the similarly highly controlled, reservation booked, Middle Fork of the Salmon River. Boating solo freed me from the hassles of raft support and the uncertain personalities of trip-mates. In 1993 I obtained a released midsummer reservation and was finally able to notch another great river with 6 days gear crammed into the oxymoronically termed stow-floats within my thunder blue Perception Dancer kayak. Calling in for cancelled permits, and having the freedom to go at will, enabled me to run the 100 mile river every few years as a kind of summer retreat. While the accommodations were spartan-like to be sure (especially when compared to the lavish ice-cooler, gourmet catered, air-mattressed - not that there's anything wrong with that! - $2500 commercial raft expeditions), the freedom of independence and relative solitude in this scenic river wilderness simply could not be beat. I'd repeated the journey a total of five times over the intervening years, until this summer it dawned on me that seven years had passed without dipping a paddle into its crystal clear waters.

...so, with the promise of a sweet flow and the curse of certain mosquito misery in the Sierra, I reaffirmed my whitewater skills with a quick tune-up trip to the Kings River, itself still running a later than average 4500 cubic feet per second, and began stalking the new Middle Fork internet reservation site for cancelled permits. What followed was two weeks of watching the river fall to what had already been predetermined to be unacceptable levels, with gear packed and at the ready in my front hall. Come the beginning of August, still without permit, I finally threw in the towel and packed rucksack and camera for a 3 to 5 day hike into Center Basin. The very afternoon before the morning I was to set foot on trail, a permit was released for a Middle Fork launch the following day. Quickly nailed down, and with gears switched yet again, my wife and I threw gear into and onto the car for the 18 hour drive to central Idaho.

Northern Nevada expanses and the obligatory pre-river stop at the Arctic Circle behind us, we rolled into the Boundary Creek launch site just before midnight of the day before launch, where we were treated to one of the most satisfying thunder and lightning displays I'd experienced in some time. Little did I know then what a bellwether of the coming week those atmospheric fireworks would become.

Launch day: several hours of squishing, squashing, mashing, and teeth-gnashing of a week's (though only planning a 5 day float) worth of food and gear into the back of my technologically ancient Perception Overflow (overflowing with gear - that is!) and checking out with the river rangers, I was finally riverine at 2:00 PM, at 2.06 feet. In my previous 5 trips, I'd only carried a camera once - and that was a waterproof disposable. This time I decided to make "photography" more of a priority and took my now antiquated waterproof Pentax Optio 3.5 megapixel point and shoot, allowing me to get video as well. I cut a small window in the chest pocket of my PFD (i.e., life jacket), from which I could hopefully shoot video while paddling. Admittedly, the POV is decidedly different from most river runners as it was 2 plus feet lower than helmet cams and a good foot and a half below my actual eye-level. Hopefully, the resulting video's slower pace might suggest a more contemplative quality as counterpoint to the typical hard rock, hero-cam videos that populate the net, as whitewater sports have been mostly portrayed.

Forgetting to trip the shutter, I jabbered for no one while running the tight third class water in the first few miles and at Velvet Falls, an ersatz Class V drop at these rather low water levels - committing nothing to video posterity. Further downriver I discovered my error, and allowed the camera to run while floating the lengthy Powerhouse Rapids (incidentally, a "tacoed" dory on the left riverbank can be seen briefly in the video). The batteries died as I reviewed the afternoon's video at my Dolly Lake Camp that night, leaving me with but one set of spares to shoot the remaining 4 days and 80 miles of scenery. I decided only to shoot stills with the sole remaining set of batteries, before retiring to yet another incredible late night thunderstorm, enjoyed almost as much as the previous night's show.

By the time I'd floated into Sunflower Hot Springs the next day, the last set of batteries were exhausted after not much more than ten still shots. I was able to revive the them only enough to take a shot or two through the next few days only by resting them. My only hope of salvaging the "photography" aspect of this journey was to buy new batteries on my fourth day at the Flying "B" Ranch, where the Forest Service was requiring all boaters stop to check in with rangers from the Bernard Creek Guard Station for fire updates and camp closures in Impassable Canyon.

A bucolic second night at Upper Jackass Flat did nothing to belie the final long-range weather forecast of less turbulent weather conditions I obtained before embarking, 4 days previous. Otters played upon a sandbar across the river from my third day's lunch stop, their luxurious coats glinting liquid sunlight, but alas, I had no ability to record them. As if courting the improving weather, thunderheads built overhead again, spitting out virga, before relenting to early evening.

The fourth morning at my Lower Grouse Creek camp dawned steely grey as cirrus and then progressive mid-level stratus lowered the sky. Hurriedly breaking camp, intermittent rain began falling as I slid my rig into leaden waters. Once again, with no power for my little electronic snapshooter, I was unable to record my run through the Middle Fork's other Class V river-wide ledge, Tappan Falls.

Miles of rain-lashed paddling brought me eventually to the Flying "B", where with two-thirds of the river behind me, I was indeed able to purchase six heavy duty 'AA' batteries at their "river store". Back in business again, I was able to continue recording the journey as originally planned. Meanwhile, skies cleared and clouded alternately throughout the afternoon. I carried on through the deep clefts of Impassable Canyon, passing many invitingly sunlit sandbars upon which I could camp, in favor of blessedly active whitewater and beautifully rendered sky and earth. I pulled into my final sandbar camp as evening showers began, setting up my tent within lulls.

Once en tent, I was pinned down by moderate rain until dark, and then throughout the night as pelting downpours of hail rode the near constant malevolence of thunderclaps and curtains of lightning. Even without its no longer extant signature burned out stump, the otherwise nondescript Lightning Strike Camp had certainly lived up to its name.

Muddy brown, turbid water overtook my camp as I broke for my final day of floating, suggesting a possible deluge fueled "blow-out" in one of the upstream tributary side canyons. I would spend much of my final river time playing tag with the slurry of suspended detritus, both making our inexorable ways towards the confluence with the Main Salmon River, it seeking its own way, as I to my journey's eventual conclusion.

1 个留言

Jim: on 一月, 2011

I hope to do a similar trip this summer.

Thanks for putting the trip report up.

Jim

加入留言:

订阅留言